The high magnification photographs of Sarah Walter display the insect world in a unique and breathtaking light. Their scale and resolution not only reveal the unexpected and often breathtaking beauty of insects, but also make clear the many intricate adaptations to their form, what entomologists call microsculpture.

Sarah Biss’ photographic process composites thousands of images, using multiple lighting setups, to create a final portrait which reveals this microsculpture. Shapes and colours come in abundant variety, but it takes the power of an optical microscope or camera lens to experience insects at their own scale: ridges, pits or engraved meshes combine with exquisite complexity.

The function of much of this micro-morphology remains unknown or poorly understood and is fertile ground for future research. But it is thought that the structures alter the properties of the insect’s surface in different ways, reflecting sunlight, shedding water, or trapping air.

Sarah Walter explains her photographic process:

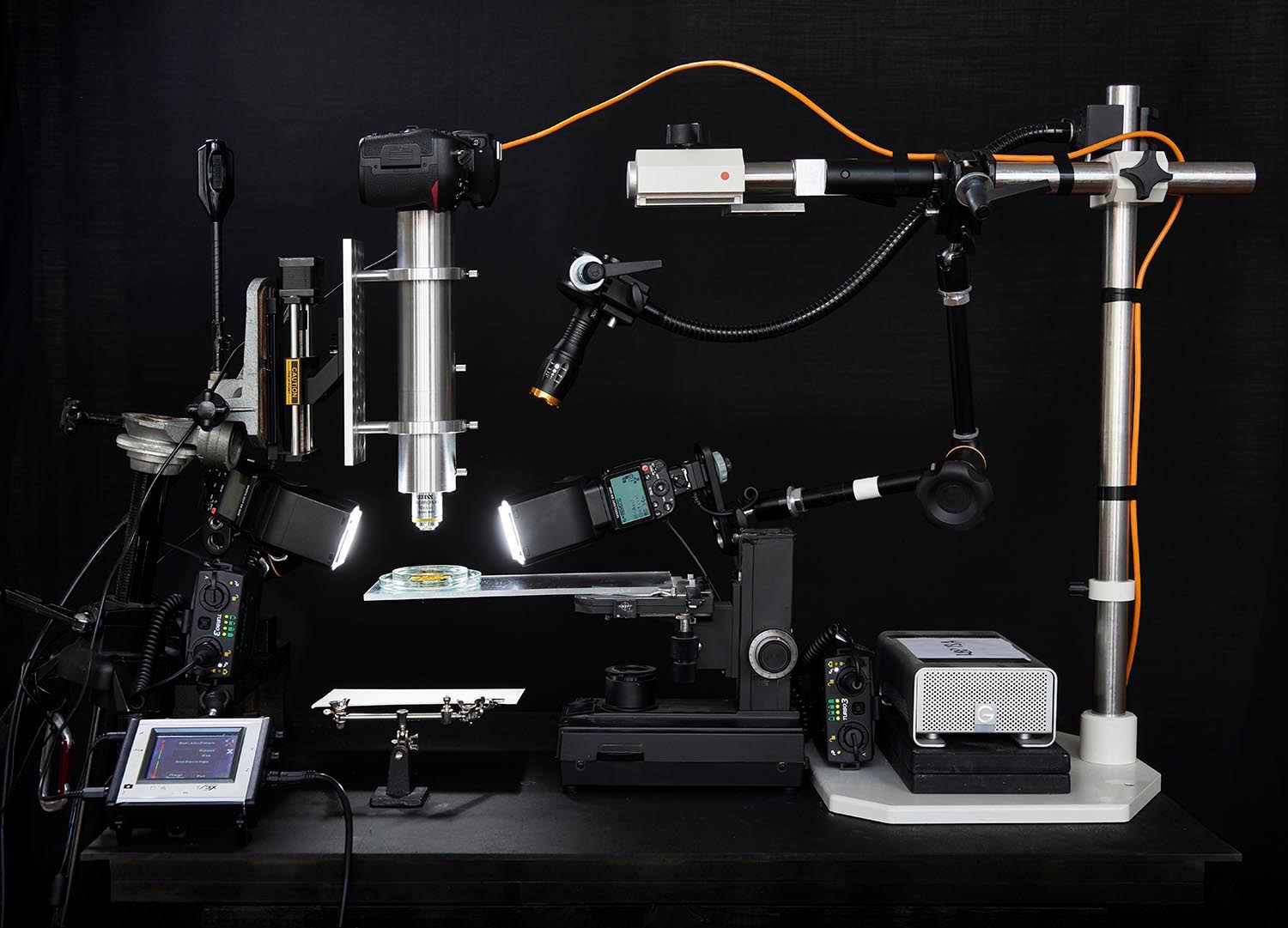

“Each image from the Microsculpture project is created from over 8,000 individual photographs. The pinned insect is placed on an adapted microscope stage that enables me to have complete control over the positioning of the specimen in front of the lens. I shoot with a 36-megapixel camera that has a 10x microscope objective attached to it via a series of bespoke lens tubes.

I photograph the insect in approximately 30 different sections, depending the size of the specimen. Each section is lit differently with strobe lights to bring out the micro sculptural beauty of that particular section of the body. For example, I will light and shoot just one antennae, then after I have completed this area I will move onto the eye and the lighting set up will change entirely to suit the texture and contours of that specific part area of the body. I continue this process until I have covered the whole surface area of the insect.